Photo by Dana Stimpson

Photo by Dana StimpsonOn my last post, I mentioned how happy I am, having such wonderful friends to explore with me the many amazing natural sites that surround us here in the northern regions of New York State. This week, my friends and I went together again to explore the beautiful Orra Phelps Nature Preserve in nearby Wilton, and that's where Dana Stimpson took the photo of rosy-cheeked me above: the happiest photo I've ever seen of myself. And one that truly reflects the delight that we were experiencing while enjoying nature together.

That's Dana in the pink hat, leaning down to observe what mosses grew on the banks of the rushing Little Snook Kill, one of two creeks that run through this lovely forested preserve, once the home of the late noted Adirondack botanizer Dr. Orra Phelps, who cherished these woodlands. It was probably Orra herself who planted the huge Rosebay Rhododendron leaning over the creek, just beyond where our friend Sue Pierce (in buffalo checks) was trying to capture in a video the icy beauty and musical sound of rushing water. Our third dear companion on this cold but gorgeous winter day was Noel Dingman, clad all in green except for her hot-pink mittens.

Before traveling further along the trail, we lingered near the creek and surrounding swale, testing ourselves to see if we could name some of the many mosses, lichens, liverworts and evergreen plants that thrive abundantly here, looking just as lush and lovely as ever, despite winter's freezing cold.

We had to brush some snow from this frilly lime-green liverwort to make sure we were indeed seeing Handsome Woollywort (Trichocolea tomentella), a plant that's as pretty as its delightful name is amusing.

This particular swale is home in spring to some of the largest, reddest Skunk Cabbage spathes I have ever found, spathes still hidden within this super-early-bloomer's winter bracts. Most of the winter bracts were as dark as the surrounding mud, unlike these two pale-green ones, protruding from a mat of bright-green Atrichum moss.

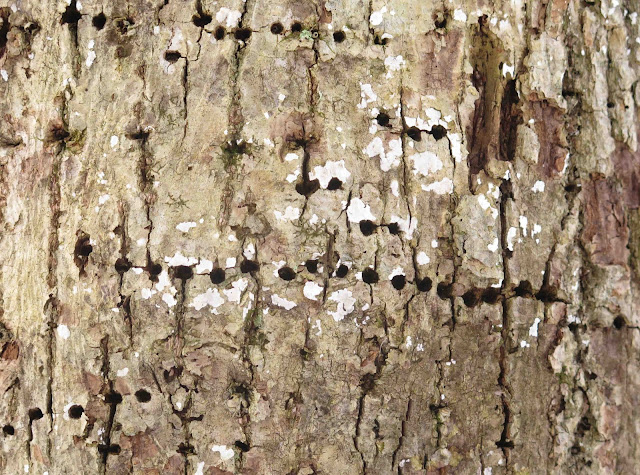

There appears to be more than one kind of moss crowning this lichen-beautified boulder. Knowing the names of neither the mosses nor the crustose pale-green and speckled lichen did not diminish my delight at this lovely co-habitation.

More crustose lichens, quite likely more than one species, decorated this boulder with a colorful pattern.

We eventually moved along to an upland woods, where each fallen log offered much to fascinate us.

Just one single limb from a fallen tree held this vividly colorful mix of various fungi and lichens: Black Witch's Butter, Red Tree Brain, and wee little Lemon Drops were the fungi; and the lichens included the bright-yellow Poplar Sunburst and some gray-green Rosette Lichens. I am not including the scientific names for any of these (their vernacular names are self-evident), because almost all fungi are now called by some other names than those in my mushroom guides. And lichens often require microscopic examination to determine their species.

Another log held these cream-colored shelf fungi with few distinguishing marks to their caps. After consulting her iNaturalist app where she shared photos of both caps and porous undersides, Sue suggested this might be the Lumpy Bracket Fungus (Trametes gibbosa).

When I turned one of the cream-colored shelf fungi over to examine its fertile surface, I was intrigued by what looked like many orange dots, a color pattern I had never observed on a mushroom before. But my camera's macro lens revealed what my un-aided poor eyesight could not see: dozens of tiny orange larvae happily feeding among the fungus's pores! Anyone know what they are? A Google search for "tiny orange larvae feeding on fungus" turned up nothing that looked like these.

At least I was sure about which understory tree produced such vividly red twigs in mid-winter. The opposite branching, large tapering oval buds, and pale bracelets ringing the twig are definite field marks for Striped Maple (Acer pensylvanicum). Not every specimen of Striped Maple bears twigs this red in winter, but I often do find thickets of red-twigged ones all growing in the same location.

Of all that enchanted us at Orra Phelps today, this rushing creek and its icy adornments provided us with probably the most delight. Recent rains had filled the creek to overflowing with rushing whitewater, and freezing nights had turned much of that water into forms of crystalline interest and beauty.

I was intrigued by how these icy forms emerging from the bank resembled in shape and striation the large shelf fungus called Ganoderma.

Where rushing water spread shallowly across plates of shale on the creek bottom, freezing had captured in dark rippling lines the rippling flow of the sheeting water.

This frieze of dangling crystal trumpets was particularly fascinating. The structure was certainly beautiful, observed from upstream, a rhythmical pattern of glassy ice, glowing with shimmering light.

From behind, this frieze was even more beautiful, animated by how the light changed from bright to dark as the rushing water rose and fell with each rippling wave. Here, the icy forms glowed with captured light.

And here, some of the bells of the trumpets grew inky black while others continued to glow with a pearly light. I was completely captivated by this beauty!

No wonder I was so thoroughly enchanted! Someone had constructed this tiny house for the woodland fairies. So perhaps the fairies were fluttering near, touching me with their magic wands and causing me to never want to leave.