Sunday, August 24, dawned as purely perfect a day for paddling as anyone could hope for: a radiant blue sky, the air sun-warmed but not too hot, and hardly a breath of breeze to ripple the glassy surface of the Hudson River in the catchment between the Feeder Dam at Moreau and the dam downstream at Glens Falls. We were planning to be a party of eight members of the Adirondack Botanical Society exploring for riverside plants, but as injury, illness, and daunting distance caused some participants to drop out, we ended up as just three happy paddlers, wondering how we could have lucked out, to be blessed with such a delightful day as this.

For being so close to a busy urban area, this stretch of the Hudson offers quite a surprising abundance of rare and unusual plants, most of which come into bloom in late August and early September. Two distinct areas within this catchment provide particularly good habitat for unusual plants. One area consists of several shallow quiet backwaters created during the historic lumbering era as basins for sorting river-driven logs. A second area consists of steep shale cliffs that are constantly watered by mineral springs, providing a cool rich habitat for many calciphile plants.

As we started our explorations, we entered a quiet backwater and immediately stopped to listen to all the birdsong emanating from many surrounding trees. Denise Griffin, a knowledgeable birder who had come all the way from near Saranac Lake, commented on how unusual it was to hear such a chorus of birds as late as mid-morning. Our friend, Sue Pierce, an Audubon member who visits these waters frequently, assured us that this area is renowned among birders as a wonderful place to see and hear birds.

One of the first unusual flowers we encountered in this backwater was the Water Marigold (Bidens beckii), which holds its bright-yellow composite blooms well above the shallow water, while trailing long masses of hair-fine leaves underwater. Although this is ranked as a rare plant in the state, it can be abundant in areas where it has found a happy home, and this Saratoga County backwater is one of those happy homes for it. (We also found one flowering individual when we paddled along the opposite Warren County shore of the Hudson.)

I was afraid we might miss seeing the rarest inhabitant of these waters, the threatened species called Small Floating Bladderwort (Utricularia radiata), since I had found it blooming here over a month ago. But there it was, holding its bright-yellow blooms above the water and drifting with the current on radiating inflated "pontoons."

Trailing along beneath the blooms and pontoons were the underwater structures consisting of hundreds of tiny bladders that can suck in and digest the minute organisms that provide the food for this leafless plant.

Although many of these riverbanks are crowded with too many shrubs of the very invasive Buckthorn, a number of native shrubs still manage to hold their own. One of these native shrubs is Wild Senna (Senna hebecarpa), which had completed its blooming some weeks ago but could still be recognized by its locust-like leaves and long bean-like pods.

Another native shrub that persists along these banks is Silky Dogwood (Cornus amomum), which now holds clusters of beautiful royal-blue fruits. Two different Viburnums, Nannyberry and Wild Raisin, also bore clusters of fruits, but their berries were still unripe. We also found Winterberry shrubs with fruits that had yet to turn their beautiful scarlet.

Along with other streamside plants like Cardinal Flower and Pickerelweed (which were also abundant along the shore), the Common Arrowhead (Sagittaria latifolia) doesn't mind having its feet wet at all.

Higher up on the banks were tall stalks of Turtlehead (Chelone glabra) just beginning to open their spikes of chubby pink-tinged blooms.

We found just small patches of Golden Pert (Gratiola aurea) in this catchment where we paddled today, perhaps because the banks are more steep and wooded than those that occur upstream above the Feeder Dam, where wide mudflats are carpeted with glowing masses of these tiny golden trumpets set among bright-green leaves.

The small white female flowers of Wild Celery (Vallisneria americana) rest just at the water's surface, held there as the water levels rise and fall by the coiling and uncoiling of their curlicue stems.

After slowly moseying around the edges of the backwaters, we headed out into the open river and leaned a little harder into our paddles to make our way upstream to where sheer cliffs of black shale rise steeply from the water's edge. These north-facing cliffs are constantly dampened by dripping mineral springs, creating a cool, wet, rich habitat for many lime-loving plants.

It was here where we found a profusion of snowy-white Grass-of-Parnassus (Parnassia glauca) growing directly out of the shale and set among gracefully curving fronds of Bulblet Fern.

The Parnassia also shared its space with masses of leafy green liverworts and clumps of dampened mosses.

(If somebody knows the names of this moss and these liverworts, I would love to have you leave this information in a comment.) Update: Be sure to click on the comments to learn what Bob D. had to say about these liverworts.

Kalm's Lobelia (Lobelia kalmii) was holding its dainty blue blooms on fine wiry stems.

Big bunches of Spikenard berries (Aralia racemosa) hung over our heads as we paddled beneath the cliffs. I have heard that the presence of Spikenard is almost always an indicator of lime in the soil (or in this case, the underlying rock). These green berries will eventually ripen to a deep shiny black.

We were surprised to see the leaves of Mountain Maple (Acer spicatum) already edged with red, reminding us that summer is indeed coming to a close very soon.

Also providing a patch of color among the cliffs was this abundant growth of the green alga called Trentepohlia aurea, a bright-orange lime-loving alga that contains a chemical that masks its green chlorophyll, which allows the orange to emerge.

After marveling at all the wondrous variety of plants that make these cliffs their home, we paddled directly across the river to the spacious lawn of a riverside park. Here we sat on the grass to enjoy a picnic lunch, savoring not just our food but also the delights of this beautiful late-summer day with congenial companions on a lovely stretch of river. And to top off our enjoyment, we heard the cheerful music of an ice-cream truck pulling into the park, and treated ourselves to an ice-cream bar for dessert.

As we made our way back to our put-in place, we drew to a halt to savor the sight of these brilliant orange mushrooms that had sprung up at the base of a tree.

I believe that this is the Jack O'Lantern fungus (Omphalotus olearius), often found clustered at the base of stumps. Sometimes confused with the edible Chanterelle, it would be a bad mistake to eat it, since this fungus is quite poisonous. I'm often tempted to pick it, however, and take it home to see if it really does glow in the dark, as all my mushroom guides tell me it does. But today I decided to leave it where it was, as part of the many riverside attractions that made this day on the river so delightful.

For more than thirty years I've been wandering the woods and waterways of Saratoga County, New York, and regions nearby, looking closely, listening carefully, and recording what I experience. We are blessed in this region with an amazing amount of wilderness right at hand. With this blog I share my year-round adventures here, seeking out what wonders await in my own Madagascar close to home.

Thursday, August 28, 2014

Tuesday, August 26, 2014

Familiar Flowers and Other Fun Finds: The Thursday Naturalists Visit Woods Hollow

It was raining so hard last Thursday morning, I didn't know if any of my friends in the Thursday Naturalists would venture out to Woods Hollow Nature Preserve for our weekly outing. But these friends are indeed a dedicated bunch, the few who showed up, and nature rewarded that dedication by diminishing the downpour to merely a wispy mist while we explored the meadow, sandplain, and forested habitats of this extensive nature preserve near Ballston Spa.

We entered the preserve through the wet meadow, a large open area abounding with such familiar sun-lovers as Boneset, Goldenrod, Black-eyed Susan, and way too many Purple Loosestrife, a beautiful but invasive species that so far seems to be held somewhat in check by the sturdy natives around it. Proliferating in the edges of this meadow were masses of Slender Gerardia, a pretty little purple flower whose delicate appearance belies its tenacious ability to thrive in hot sandy areas of sterile soil.

This next flower was hiding among shrubs and tall grasses, but the deep musky fragrance of Groundnut alerted us to its presence before we even caught sight of its oddly convoluted florets.

When we reached the drier sandplain area of Woods Hollow, we were greeted by the sight of dozens and dozens of plants of Blue Curls, all still holding on to their dainty blue flowers that, on a sunnier day, would have dropped to the ground by mid-day.

This is a flower that deserves a closer look, to observe the gracefully curving anthers that suggested this species' common name, as well as to admire the pretty speckles on the flower's lower lip.

Horsemint is another denizen of such dry sandy habitats, and we were surprised to see so many still blooming at this late date. The actual flowers, yellow blooms covered with red spots, hide in the axils between the far showier pinkish bracts of this extremely aromatic plant.

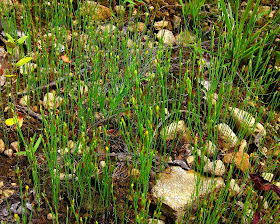

It was easy to miss the slender blooming spikes of Sand Jointweed, almost invisible against the sand, but once we saw one, we found them again and again.

Winged Pigweed is a bushy plant of sandpits, roadsides, and other "waste places," and it's certainly thriving at Woods Hollow. Three years ago, I found here just a single specimen of this plant, a native of America's central plains that has made its way east in recent decades, and by now, the plant has established quite a colony. As it matures, it will break off at its central stalk and roll away like a tumbleweed, dropping its many seeds along the way.

When Butterfly Weed is in bloom, its bright-orange blooms are impossible to overlook, and its distinctive spiky seedpods are also easy to spot from some distance away.

In addition to finding many of our favorite late-summer flowers in bloom and in seed, we enjoyed spotting some interesting fauna among the flora. I can't believe I actually captured an image of this Praying Mantis, it was scurrying so quickly among the blades of grass, trying to escape my prying lens.

Ooh, what's this colorful spiky bug that's crawling across this oak leaf? Someone in our group suggested it might be a Ladybug larva, and when I googled that guess, I found many images that looked exactly like this. Yes, the larval form of the Seven-spotted Ladybug. Isn't it amazing how different the adult looks from its larva?

Yes, and the adult Milkweed Tiger Moth, with its dusty gray/brown wings, certainly looks quite different than its larva, too, seen here in this photo below. This rather soggy furry caterpillar was feasting on a milkweed leaf, absorbing the toxins that will protect it from predators, warning them off by its vivid tiger-striped orange and black coloration.

We found a number of interesting fungi sprouting up from the wet sand, but this hard knobby one was by far the most fascinating. It didn't look like much at first, just a sandy-brown ball sitting atop the similar-colored sand. When we picked it up, we saw that it had no stalk, no gills, and no pores. And then Tom took out his knife and cut it open.

Wow! What a fascinating structure of tiny spheres packed inside! We had never seen anything like it, but later we heard from our friend Lois, who had sone some research and suggested it might be the fungus called the Dyemaker's Puffball (Pisolithus tinctorius).

After searching various sites on the internet, I do believe Lois is correct. To learn all about this fascinating fungus, which has indeed been used to produce a dark reddish dye for wool, visit Tom Volk's Fungi. He has some funny stories to tell about finding this fungus.

We entered the preserve through the wet meadow, a large open area abounding with such familiar sun-lovers as Boneset, Goldenrod, Black-eyed Susan, and way too many Purple Loosestrife, a beautiful but invasive species that so far seems to be held somewhat in check by the sturdy natives around it. Proliferating in the edges of this meadow were masses of Slender Gerardia, a pretty little purple flower whose delicate appearance belies its tenacious ability to thrive in hot sandy areas of sterile soil.

This next flower was hiding among shrubs and tall grasses, but the deep musky fragrance of Groundnut alerted us to its presence before we even caught sight of its oddly convoluted florets.

When we reached the drier sandplain area of Woods Hollow, we were greeted by the sight of dozens and dozens of plants of Blue Curls, all still holding on to their dainty blue flowers that, on a sunnier day, would have dropped to the ground by mid-day.

This is a flower that deserves a closer look, to observe the gracefully curving anthers that suggested this species' common name, as well as to admire the pretty speckles on the flower's lower lip.

Horsemint is another denizen of such dry sandy habitats, and we were surprised to see so many still blooming at this late date. The actual flowers, yellow blooms covered with red spots, hide in the axils between the far showier pinkish bracts of this extremely aromatic plant.

It was easy to miss the slender blooming spikes of Sand Jointweed, almost invisible against the sand, but once we saw one, we found them again and again.

Winged Pigweed is a bushy plant of sandpits, roadsides, and other "waste places," and it's certainly thriving at Woods Hollow. Three years ago, I found here just a single specimen of this plant, a native of America's central plains that has made its way east in recent decades, and by now, the plant has established quite a colony. As it matures, it will break off at its central stalk and roll away like a tumbleweed, dropping its many seeds along the way.

When Butterfly Weed is in bloom, its bright-orange blooms are impossible to overlook, and its distinctive spiky seedpods are also easy to spot from some distance away.

In addition to finding many of our favorite late-summer flowers in bloom and in seed, we enjoyed spotting some interesting fauna among the flora. I can't believe I actually captured an image of this Praying Mantis, it was scurrying so quickly among the blades of grass, trying to escape my prying lens.

Ooh, what's this colorful spiky bug that's crawling across this oak leaf? Someone in our group suggested it might be a Ladybug larva, and when I googled that guess, I found many images that looked exactly like this. Yes, the larval form of the Seven-spotted Ladybug. Isn't it amazing how different the adult looks from its larva?

Yes, and the adult Milkweed Tiger Moth, with its dusty gray/brown wings, certainly looks quite different than its larva, too, seen here in this photo below. This rather soggy furry caterpillar was feasting on a milkweed leaf, absorbing the toxins that will protect it from predators, warning them off by its vivid tiger-striped orange and black coloration.

We found a number of interesting fungi sprouting up from the wet sand, but this hard knobby one was by far the most fascinating. It didn't look like much at first, just a sandy-brown ball sitting atop the similar-colored sand. When we picked it up, we saw that it had no stalk, no gills, and no pores. And then Tom took out his knife and cut it open.

Wow! What a fascinating structure of tiny spheres packed inside! We had never seen anything like it, but later we heard from our friend Lois, who had sone some research and suggested it might be the fungus called the Dyemaker's Puffball (Pisolithus tinctorius).

After searching various sites on the internet, I do believe Lois is correct. To learn all about this fascinating fungus, which has indeed been used to produce a dark reddish dye for wool, visit Tom Volk's Fungi. He has some funny stories to tell about finding this fungus.

Wednesday, August 20, 2014

Traveling Plants

I think of Rte. 50 going north out of Saratoga as "Disjunct Highway," since it's along this stretch of rural road that I've found several species of plants that really don't belong in Saratoga County, even though they may be native to other parts of New York State. On this beautiful blue-sky day, I decided to visit these plants again and see how they might be prospering. Or not.

The first oddball that caught my eye back in 2011 was a single stalk of Tall Ironweed (Vernonia gigantea), towering over all other plants at the Gick Farm parking area for the Wilton Wildlife Preserve and Park. Friends from more southern states like Ohio or Pennsylvania can hardly believe that this plant could be classified as "Endangered" in New York, since it's a very common, even invasive weed where my friends live. I suppose it might eventually make its way north in time, since it certainly appears to be thriving here at this single spot in Saratoga County, quite possibly introduced with the native grass seeds sown at this grasslands restoration site.

Each year since I first saw it, it has grown another sturdy stalk, so that this year there are four, each bearing a thick cluster of fluffy magenta blooms. All four stalks, though, appear to be growing from a single plant, and I find no other plants nearby. So its shed seeds haven't traveled far, it seems, or haven't germinated wherever they might have fallen.

The same year I found the Ironweed, I discovered a second disjunct plant growing almost at the foot of the Ironweed. This was a single bloom of Late Purple Aster (Symphyotrichum patens), a species of aster native to more southern parts of New York State but not at that time recorded for Saratoga County. When I returned to the site in 2012, I found again just a single plant, but this time it had two blooms, as well as a healthy cluster of other buds. So it looked as if it might be thriving. Here's what it looked like then:

I was disappointed when I returned in 2013 and found no trace of this aster at all. So I wasn't really expecting to see it this year, either, and it certainly wasn't holding any pretty purple blooms above the grass. But a quick search of the area did reveal the presence of two plants that bore the distinctive soft-hairy ovate leaves completely surrounding a wiry rough stem. No sign of any flowers, though, and the plants did not look that robust. I wonder if I will ever see them in bloom again.

In 2012, I had found a third disjunct plant a few miles south, where a huge patch of bright-yellow Wingstem (Verbesina alternifolia) was completely filling a ditch at the intersection of Rte. 50 with Ingersol Road. After using my Newcomb's Wildflower Guide to key it out, I discovered that this was a wildflower native to the northeast, but a search of the New York Flora Association floral atlas informed me that it was not native to New York, although it had been introduced in just a few counties. As it apparently had been here. The same patch I found two years ago was continuing to thrive today.

As I passed this Wingstem ditch and noted that the flowers were blooming, I cast my eyes around the neighboring landscape and noticed another patch of tall yellow flowers on the opposite side of the road. Pulling over, I got out and climbed a bank to investigate, and, sure enough, here were the swept-back yellow composite blooms and distinctively flanged stems that could only belong to Wingstem.

A little further investigation revealed that Wingstem was everywhere to be found on this little farm.

Hoping I might find the inhabitant of this charming property who might be able to tell me how this Wingstem came to thrive here, I continued along a path that took me past a vegetable garden as well as some buzzing beehives. Then I found a small white house with a table of garden produce arrayed for sale, and I thought, Aha! Here's the excuse I need to knock on the door.

Well, I didn't even need to knock before Mr. Donald Tooker emerged from the house to greet me at his small produce stand. Of course, I bought a few items to take home for supper, but what I was even happier to take home was Mr. Tooker's tale of how he had spent his whole life on this farm and the various ways he had farmed it. We spent a good half-hour conversing about dairy farming and beef cattle and bee-keeping and how the surrounding landscape had changed since he was born right here in this very place. And he seemed quite happy to chat with me and answer my every question.

Mr. Tooker seemed to be quite amused when I asked him how the Wingstem came to thrive here. "Why yes," he said, a bit amazed that I knew the name of this flower, "the Wingstem was for the BEES!" Did I not know that Wingstem was famous among beekeepers for making wonderful honey? Indeed, I did not, but I wasn't surprised, considering how many bees I had seen buzzing among its towering blooms. Mr. Tooker had found the seed advertised in a beekeeper's publication, and it was he himself who, oh maybe 30 or 40 years ago, had plowed up the patch across the road and scattered the seed. He had planted more around the honey-processing shed, and from there it just grew like a weed.

The first oddball that caught my eye back in 2011 was a single stalk of Tall Ironweed (Vernonia gigantea), towering over all other plants at the Gick Farm parking area for the Wilton Wildlife Preserve and Park. Friends from more southern states like Ohio or Pennsylvania can hardly believe that this plant could be classified as "Endangered" in New York, since it's a very common, even invasive weed where my friends live. I suppose it might eventually make its way north in time, since it certainly appears to be thriving here at this single spot in Saratoga County, quite possibly introduced with the native grass seeds sown at this grasslands restoration site.

Each year since I first saw it, it has grown another sturdy stalk, so that this year there are four, each bearing a thick cluster of fluffy magenta blooms. All four stalks, though, appear to be growing from a single plant, and I find no other plants nearby. So its shed seeds haven't traveled far, it seems, or haven't germinated wherever they might have fallen.

The same year I found the Ironweed, I discovered a second disjunct plant growing almost at the foot of the Ironweed. This was a single bloom of Late Purple Aster (Symphyotrichum patens), a species of aster native to more southern parts of New York State but not at that time recorded for Saratoga County. When I returned to the site in 2012, I found again just a single plant, but this time it had two blooms, as well as a healthy cluster of other buds. So it looked as if it might be thriving. Here's what it looked like then:

I was disappointed when I returned in 2013 and found no trace of this aster at all. So I wasn't really expecting to see it this year, either, and it certainly wasn't holding any pretty purple blooms above the grass. But a quick search of the area did reveal the presence of two plants that bore the distinctive soft-hairy ovate leaves completely surrounding a wiry rough stem. No sign of any flowers, though, and the plants did not look that robust. I wonder if I will ever see them in bloom again.

In 2012, I had found a third disjunct plant a few miles south, where a huge patch of bright-yellow Wingstem (Verbesina alternifolia) was completely filling a ditch at the intersection of Rte. 50 with Ingersol Road. After using my Newcomb's Wildflower Guide to key it out, I discovered that this was a wildflower native to the northeast, but a search of the New York Flora Association floral atlas informed me that it was not native to New York, although it had been introduced in just a few counties. As it apparently had been here. The same patch I found two years ago was continuing to thrive today.

As I passed this Wingstem ditch and noted that the flowers were blooming, I cast my eyes around the neighboring landscape and noticed another patch of tall yellow flowers on the opposite side of the road. Pulling over, I got out and climbed a bank to investigate, and, sure enough, here were the swept-back yellow composite blooms and distinctively flanged stems that could only belong to Wingstem.

A little further investigation revealed that Wingstem was everywhere to be found on this little farm.

Hoping I might find the inhabitant of this charming property who might be able to tell me how this Wingstem came to thrive here, I continued along a path that took me past a vegetable garden as well as some buzzing beehives. Then I found a small white house with a table of garden produce arrayed for sale, and I thought, Aha! Here's the excuse I need to knock on the door.

Well, I didn't even need to knock before Mr. Donald Tooker emerged from the house to greet me at his small produce stand. Of course, I bought a few items to take home for supper, but what I was even happier to take home was Mr. Tooker's tale of how he had spent his whole life on this farm and the various ways he had farmed it. We spent a good half-hour conversing about dairy farming and beef cattle and bee-keeping and how the surrounding landscape had changed since he was born right here in this very place. And he seemed quite happy to chat with me and answer my every question.

Mr. Tooker seemed to be quite amused when I asked him how the Wingstem came to thrive here. "Why yes," he said, a bit amazed that I knew the name of this flower, "the Wingstem was for the BEES!" Did I not know that Wingstem was famous among beekeepers for making wonderful honey? Indeed, I did not, but I wasn't surprised, considering how many bees I had seen buzzing among its towering blooms. Mr. Tooker had found the seed advertised in a beekeeper's publication, and it was he himself who, oh maybe 30 or 40 years ago, had plowed up the patch across the road and scattered the seed. He had planted more around the honey-processing shed, and from there it just grew like a weed.

Sunday, August 17, 2014

New Finds on the High Powerline

The almost-autumnal weather of late was perfect for climbing a steep rocky powerline this past Saturday. My friend Sue and I had climbed up these slopes in late June, when we hid from the sun as much as we could in the deep woods surrounding the clear-cut. But on this pleasantly cool afternoon, the intermittent sun felt welcome as we scrambled up tumbled rocks and pushed our way through hip-deep ferns and flowers.

I was on a mission to find two plants we had located in June, hoping to find them in bloom so that I could collect some specimens to update the botanical atlas for Saratoga County. Neither Prostrate Tick-trefoil (Desmodium rotundifolium) nor Orange-grass St. Johnswort (Hypericum gentianoides) appear on the New York Flora Association's distribution maps for the county, although we had found both species growing abundantly up here in June (albeit without any flowers at that time).

Having seen it before at another location, I knew that the Orange Grass bloomed in late summer/early autumn, but I was only guessing about the bloom time for the Prostrate Tick-trefoil, a species unfamiliar to me. As it happened, I was just beginning to fear we had missed its bloom time, since all I was finding were its yellowing leaves and a few seedpods, when Sue spotted several blooms at the ends of long trailing stems. I was able to get a photo as well as collect a blooming specimen. Prostrate Tick-trefoil is not a rare plant in New York, but this is the only site where I have ever found it.

I had hoped we would find both plants in bloom together, since it's quite a hike to get up to their locations. But when we found a large patch of the Orange Grass, I was disappointed to find it still in bud, with no open flowers. The yellow buds would probably open wide in a day or two, with many other buds still closed up tight within their deep-red sepals.

On second thought, though, I wonder if the deep-red "buds" are not sepals at all, but instead the seedpods of spent blooms. Perhaps if the day had been warmer, all those yellow buds would have been open wide. After searching, I did find a few tiny flowers just starting to spread their petals.

The Prostrate Tick-trefoil had been a new "lifer" for Sue and me when we found it last June, and this August afternoon yielded yet another flower that neither I nor Sue had ever seen before. And believe me, it would have been hard to miss the giant, vividly-colored blooms of Pasture Thistle (Cirsium pumilum), a low-growing thistle native to the northeastern U.S.

Although the whole plant was barely two-feet high, the blooms were the largest thistle flowers I have ever seen, and they were delightfully fragrant as well as beautiful.

That gorgeous thistle alone would have made our efforts worth the trip, but we were also pleased to find many other flowers in bloom, including several other species of Tick-trefoil. These bright-pink flowers were among the widely-branched blooms of Panicled Tick-trefoil (D. paniculatum).

The flowers of Large-bracted Tick-trefoil (D. cuspidatum) were paler and bluer and borne in a tighter cluster than those of D. paniculatum. The leaves are much larger and wider, too, and they narrow to sharp, rather than rounded, points.

Bush Clovers (Lespedeza) were abundant up here on this high open meadow, but they were not the Round-headed ones we were used to commonly seeing at other locations. Here we found Hairy Bush Clover (L. hirta), with its dense spike-like clusters of white flowers touched with pink, and with obviously hairy stems.

Here too, we found the pretty purple blooms of Wandlike Bush Clover (L. intermedia).

Bright yellow sprays of Goldenrod waved in the breeze, which did not interrupt the amorous activities of many pairs of Goldenrod Soldier Beetles.

I hope our pairs of insect lovers manage to escape the clutches of this Goldenrod Crab Spider camouflaged amid the golden florets. But since this little tyke was hardly a quarter inch across, perhaps it lies in wait for smaller prey.

Update: As my friend Sue notes in her comment to this post, this little spider is NOT a Goldenrod Crab Spider, but rather a White-banded Crab Spider (Misumenoides formosipes). According to a very informative website Sue cites, "a view of the eyes from the front can distinguish this species from the similar looking Goldenrod crab spider (Misumena vatia). In the White-banded crab spider, there is a conspicuous, white, transverse ridge below the eyes called a 'clypeal carina.' Misumena vatia does not have such a ridge."

This colorful critter would not be preying on either the spider or the mating beetles, since the Banded Net-winged Beetle dines mostly on nectar or the juices of rotting plants. It's unusual to see a beetle without hard shiny wing covers, but that's how it came to be called a net-winged beetle.

As Sue and I started back down the mountain, we stopped to enjoy the view of the shining river from our high prospect. I very stupidly forgot to carry my GPS device to record the coordinates of where I found the plant specimens I collected, so I shall have to return to make those readings at a later date. Perhaps I will wait until autumn turns the mountainside forest to gorgeous colors. Can you imagine how lovely this view will be then?

I was on a mission to find two plants we had located in June, hoping to find them in bloom so that I could collect some specimens to update the botanical atlas for Saratoga County. Neither Prostrate Tick-trefoil (Desmodium rotundifolium) nor Orange-grass St. Johnswort (Hypericum gentianoides) appear on the New York Flora Association's distribution maps for the county, although we had found both species growing abundantly up here in June (albeit without any flowers at that time).

Having seen it before at another location, I knew that the Orange Grass bloomed in late summer/early autumn, but I was only guessing about the bloom time for the Prostrate Tick-trefoil, a species unfamiliar to me. As it happened, I was just beginning to fear we had missed its bloom time, since all I was finding were its yellowing leaves and a few seedpods, when Sue spotted several blooms at the ends of long trailing stems. I was able to get a photo as well as collect a blooming specimen. Prostrate Tick-trefoil is not a rare plant in New York, but this is the only site where I have ever found it.

I had hoped we would find both plants in bloom together, since it's quite a hike to get up to their locations. But when we found a large patch of the Orange Grass, I was disappointed to find it still in bud, with no open flowers. The yellow buds would probably open wide in a day or two, with many other buds still closed up tight within their deep-red sepals.

On second thought, though, I wonder if the deep-red "buds" are not sepals at all, but instead the seedpods of spent blooms. Perhaps if the day had been warmer, all those yellow buds would have been open wide. After searching, I did find a few tiny flowers just starting to spread their petals.

The Prostrate Tick-trefoil had been a new "lifer" for Sue and me when we found it last June, and this August afternoon yielded yet another flower that neither I nor Sue had ever seen before. And believe me, it would have been hard to miss the giant, vividly-colored blooms of Pasture Thistle (Cirsium pumilum), a low-growing thistle native to the northeastern U.S.

Although the whole plant was barely two-feet high, the blooms were the largest thistle flowers I have ever seen, and they were delightfully fragrant as well as beautiful.

That gorgeous thistle alone would have made our efforts worth the trip, but we were also pleased to find many other flowers in bloom, including several other species of Tick-trefoil. These bright-pink flowers were among the widely-branched blooms of Panicled Tick-trefoil (D. paniculatum).

The flowers of Large-bracted Tick-trefoil (D. cuspidatum) were paler and bluer and borne in a tighter cluster than those of D. paniculatum. The leaves are much larger and wider, too, and they narrow to sharp, rather than rounded, points.

Bush Clovers (Lespedeza) were abundant up here on this high open meadow, but they were not the Round-headed ones we were used to commonly seeing at other locations. Here we found Hairy Bush Clover (L. hirta), with its dense spike-like clusters of white flowers touched with pink, and with obviously hairy stems.

Here too, we found the pretty purple blooms of Wandlike Bush Clover (L. intermedia).

Bright yellow sprays of Goldenrod waved in the breeze, which did not interrupt the amorous activities of many pairs of Goldenrod Soldier Beetles.

I hope our pairs of insect lovers manage to escape the clutches of this Goldenrod Crab Spider camouflaged amid the golden florets. But since this little tyke was hardly a quarter inch across, perhaps it lies in wait for smaller prey.

Update: As my friend Sue notes in her comment to this post, this little spider is NOT a Goldenrod Crab Spider, but rather a White-banded Crab Spider (Misumenoides formosipes). According to a very informative website Sue cites, "a view of the eyes from the front can distinguish this species from the similar looking Goldenrod crab spider (Misumena vatia). In the White-banded crab spider, there is a conspicuous, white, transverse ridge below the eyes called a 'clypeal carina.' Misumena vatia does not have such a ridge."

This colorful critter would not be preying on either the spider or the mating beetles, since the Banded Net-winged Beetle dines mostly on nectar or the juices of rotting plants. It's unusual to see a beetle without hard shiny wing covers, but that's how it came to be called a net-winged beetle.

As Sue and I started back down the mountain, we stopped to enjoy the view of the shining river from our high prospect. I very stupidly forgot to carry my GPS device to record the coordinates of where I found the plant specimens I collected, so I shall have to return to make those readings at a later date. Perhaps I will wait until autumn turns the mountainside forest to gorgeous colors. Can you imagine how lovely this view will be then?

.jpg)